SPOILER ALERT! This post contains details from the Netflix series Boots.

Andy Parker didn’t set out to incite more debate about the U.S. military with his Netflix series Boots, and he certainly didn’t anticipate that the Pentagon would weigh in on it, but he also can’t say he’s all that surprised by the dust the series has kicked up, either.

“I do think that just the premise of the show, before you engage with it, before you really know what it is, incites a reaction and assumptions,” he admitted during a recent chat with Deadline.

Those reactions and assumptions have come from across both sides of the political aisle as conversation swirls around the loose adaptation of Greg Cope White’s memoir The Pink Marine, about a gay man who joins the U.S. Marine Corps in 1990, at a time when it was still illegal to be gay in the military. There are those who say that the series is not quite critical enough of the armed forces. Then, there’s the folks, like those at the Pentagon, who think the series is “woke garbage.”

Whatever the assumptions, the discourse has certainly elevated the profile of the modest series, which is the last project produced by Norman Lear before his death. After nearly doubling its viewership last week, Boots managed another 5.6M views from October 20 to October 26, per Netflix’s latest weekly TV rankings, putting it at No. 3 in its third week on the streamer — ahead of Ryan Murphy’s buzzy Monster: The Ed Gein Story.

Netflix has also been intentional about the rollout for the title. While Boots is tonally quite sardonic at times, Parker, as well as those involved with the marketing campaign for the title, wanted to ensure that they took seriously the queer stories at the center of the series.

Ahead of premiere, Netflix launched a trailer featuring a cover of George Michael’s “Freedom! ’90” from the San Diego Gay Men’s Chorus. Deadline also understands that the company worked mainly with queer crews, artists and strategists the help run the campaign behind-the-scenes. That’s in addition to queer actors depicting all of the queer characters in the show.

In the interview below, Parker spoke with Deadline about the response to Boots, some of the most pivotal creative decisions in Season 1, and the future of the series.

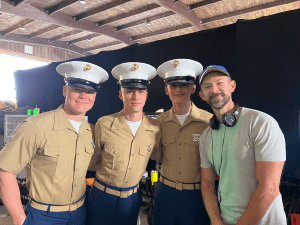

From left: Angus O’Brien, Miles Heizer, Liam Oh, and Andy Parker on the set of Boots (Courtesy of Netflix)

DEADLINE: I was expecting the show to be quite tongue-in-cheek, but there was a level of earnestness to its depiction of the military and the people in it that I was not quite expecting. When developing the series, how did you want to strike that tonal balance?

ANDY PARKER: I knew early on, if this was going to be a show about a queer kid joining the military, that there was going to be a different sensibility to the show than all the other military media that we’ve seen a lot of, which is very iconic and memorable. For me, the reason to go back into that territory was to go through this queer lens, this new point of view. That, to me, felt like there was automatically a different sensibility at work. There was also a sort of spark or energy in Greg Cope White’s memoir. There was this sardonic commenting on what was happening that I really appreciated…when I went to pitch the show originally, I pitched it as Full Metal Jacket as told by David Sedaris, and that is very much the tension that I think is useful to bring into this world that is so harrowing, that is so daunting and relentless. I think that was one way to make sure that we weren’t doing the same bleak and tyrannical take on the military again — it’s interesting, the word earnest, I think a lot of people would turn up their nose at the word earnest and find that sort of pejorative in a way. I embrace that, and I appreciate you using it, because I think what we’re after is a genuine and authentic emotional experience.

That, for me, was always what I wanted to achieve. Yes, there was going to be this sardonic quality to it, this referential, winking idea, but when you peel that all away, there was going to be a very poignant story, it seemed, to me, of somebody having to reckon with themselves. I don’t know what is more earnest than that, than the reckoning that ends up happening when all your comforts are stripped away, and you’re left with this confrontation, and adding to that the relationships and bonds that you’re forming along the way with the other recruits. So I wanted it to be a true coming-of-age ensemble story. With that, you’re heading into earnest terrain. I think the way to keep it from being maudlin or corny or silly is to inject it both with the real stakes of boot camp, which are genuinely harrowing, and then with this off-center humor and this queer sensibility. The combination of those things, I think, is what gives the show it’s special sauce. It seems to be surprising people. That’s the thing that I’m so heartened by, is that people come to the show hearing a log line, and they think, ‘Oh, this is not what I expected it to be. Now it’s 3 a.m., and I’m weeping.’ I love that people are getting pulled into the surprise of what the show really is.

DEADLINE: I keep coming back to the scene in the finale where Cameron is running across the finish line after finishing the crucible. It’s a very human moment. It’s an interesting lens from which to discuss the U.S. military, and particularly problems within the military, especially in this political climate. How’d you ensure your focus remained on the people at the center of this story, rather than getting caught up in the more existential and institutional lens that we often view and discuss the military through?

PARKER: I think, ultimately, what we’re after is this emotional journey, giving our viewers a cathartic experience. The way that you do that, I think, is to invest in these characters and make sure that we are rooted in an understanding of who they are and what their obstacles are and take them on a journey that we’re going to have to partake in and go [through] the highs and lows. That emotional roller coaster, I think, was paramount there. There is a political, institutional dimension, of course, to all of this, because of the time and place and circumstance that we’re dealing with. But I never set out to make a polemic. Some people have come to the show disappointed that it’s not the scathing takedown of the military. Queer people exist. The military exists. Some people are bothered that queer people exist, and some people are bothered that the military exists. We live in a world where both exist, and we have to reckon with that. The show is looking at what it feels like to be in 1990 and to be asked to hide who you are and deny who you are in order to get the things that the military is offering you, which are in some cases really noble, good things for this particular character at this particular time in his life. I think that’s a really rich and interesting conundrum. I want to watch the emotional and moral and ethical journey of that character.

So, while I understand that some people want the show to be more of an indictment against the system, I think the show still has more to say. I think where we leave Cameron at the end of the of Season 1, he has achieved this real victory. It is a very hard thing to get through those 13 weeks of boot camp, especially for this kid who we never thought would even make it. But at the end of the season, what I hope viewers are left with is to feel the question of: Is this good for Cameron’s soul? Now that he’s achieved this thing, what’s going to happen now that he’s a Marine, now that he might actually have to go serve, not just in peacetime, but potentially in wartime? I think there’s more. Cameron’s education is not complete, and I think we, as an audience, have to go through that reckoning with him as well as he continues his career in the Marines and as he continues to live out the bargain that he’s made with the Marines.

DEADLINE: To that point, I was surprised that the show ends on such a grounded note. This celebratory moment they are having is undercut by the news reports about the escalation of the Gulf War, which really bring everyone back to reality. Can you tell me why you wanted to end it there?

PARKER: Boot camp is this cocoon, and necessarily, right? You are sucked away from real life, from normal life, in order to be put in this machine that transforms you. You are so steeped in, and you’re so consumed by what the Marines are giving you and the training that you’re receiving, so that at the end of it, you can come out a different person, and you can wear that uniform, and you can know what to do. But, they don’t really, fully know yet what it is to be a Marine — and certainly not what it is to be a Marine in combat. So you can have that achievement, you can have that victory and still know that there’s so much more to learn. There’s so much more to be challenged with every single one of those characters. [They each come] into boot camp with some sort of secret or something to hide or something to confront. I think we have a lot more to continue to unpack from each one of those [characters], because they’ve only just dipped the toe in. Even though this is a momentous thing that they’ve done, they haven’t done the real thing yet.

DEADLINE: So, as you said, there have been some people saying that the series isn’t critical enough of the military. On the other hand, the Pentagon weighed in last week and called it “woke garbage.” It seems like, in some ways, it’s pissed off both sides of the political aisle. What has that illuminated for you about the story that you set out to tell that you maybe didn’t even fully realize until it became embroiled in all this discourse?

PARKER: I think I anticipated both sides of the reaction, frankly, because I do think that just the premise of the show, before you engage with it, before you really know what it is, incites a reaction and assumptions. I think people come to the show with their own meanings and assumptions. But what has been so delightful and heartening to me is…to watch people be so surprised and taken by it, and really, I think, seduced by the love that they come to find for these characters. Having an empathetic experience, to me, is what the show is for. It is not here to make a political case, but it is here to help you have an emotional and empathetic experience. I think the show does have something to say about our current political time, but I’m going to let the show speak to that, and I’m going to let people feel that more than comment on it or be overt and strident in its approach. I don’t walk around in my normal life with a sense of deep solidarity with mankind. I think that’s probably why I’m a writer, but what the response to the show from [people] all over, all kinds of walks of life, civilians, veterans, all different kinds of political persuasions, that broad response has shocked me and has made me feel connected to people in a way that I haven’t before. So, talk about an earnest sentiment. That’s been my experience over the last few weeks of watching and listening to people’s reactions. I think telling stories of connection, and that connection is possible, and connection across divides is possible…the fact that these young men are so different and come from so many different places, and yet, they are unified by the end of this [because of] the brotherhood and mission and purpose. I need that kind of story right now myself.

DEADLINE: There’s a line in the show that ‘boot camp is the machine that makes men.’ It really struck me, because as I watched the show and as the stories about Cameron and several other gay men in the military unfolded, I found myself wondering what that means. What does it mean to be a “man” in the military? What is the role of masculinity in the military? I know you had several former Marines in the writers room with you. Did they weigh in on this?

PARKER: We did have three Marines in the writers room. One of them was a woman, a female officer named Megan Carol Burke, and so her perspective was also very integral to all of us. I don’t think the show has any easy answers or wants to have a thesis, necessarily, about what masculinity is or should be, but there is obviously, in the Marine Corps, a sort of textbook way of performing it all. What we watch in the show is people performing it, and then…the real moments of growth happen when people take off the mask or step around the role and actually relate to each other with vulnerability or with some sort of risk of like, ‘I’m putting myself out here, hoping that you see me and recognize me.’ In these moments of grace, in between the performance of the brutality or the violence or all of those masks of strength that they’re encouraged to wear and display, the fact that it is in those moments of softness, or seeming softness, that something breaks through, that something grows — I think that, to me is what is really important about what the show is. We’re trying to question, I guess.

DEADLINE: This is the last show that the late Norman Lear produced. It seems very fitting, especially given the dust it has kicked up, considering he was not one to shy away from hard topics. How have you reflected on that collaboration more deeply now that you’ve watched this discourse unfold with Boots?

PARKER: I’m so proud of how the show is giving space for some of those conversations I’ve had [and] anecdotes from people I know who reached out to say that the show has opened, in their own lives, opportunities for conversation that they didn’t think that they would be getting to have. I can’t think of anything better to attribute to a Norman Lear show than than that. It seems to me that that is, other than just pure entertainment, why we should be making stories. The challenge that Norman issued to us was to make something meaningful, and I can only hope that it is giving people the space to reconsider their own assumptions about masculinity, or their sense of what it means to be an American, or their patriotism, or reflect on who’s volunteering to serve and defend the country. It’s been incredibly meaningful to me to hear from people. I have to be honest, I didn’t anticipate that being such a powerful part of this release.

DEADLINE: To your point about what it means to be an American, the show certainly comes at a time when many people are questioning that — and also maybe wavering in their pride for the country. What did you want to say, through the show, about what it means to be American?

PARKER: To bring it back to Norman Lear, one of the first things I said to him when I was talking to him about why I wanted to adapt the book and do the show, [was that] one of the things I think this is about is who gets to be counted as an American. That struck such a chord with him, because I think so much of his work has been about that definition, about that question, and making sure that definition continues to expand and not contract. So, we’re in the middle of the debate about whether that should be expanded or contracted, and who gets to decide that, and who gets to make those determinations. One of the quotes from the show that I really like is, in the fourth episode, Cameron standing in a dumpster, and Sullivan is giving him what ultimately we find out is some tough love, and he says, ‘Claim your f*cking place.’ So there is an element of of asking for inclusion, and there’s also an element of claiming your f*cking place. I think that is going to continue to be a dialogue that America is going to have with itself, probably forever.